Why Fred Karger Isn’t Just Tilting at Windmills

by Karen Ocamb on January 23, 2012

For link to story, CLICK HERE.

This article is from the new issue of Frontiers magazine.

Reading his email dispatches as he traveled to Iowa, New Hampshire and now Michigan for his Republican presidential campaign, it’s easy to think of Fred Karger as a modern-day Don Quixote. Surely, like the fictional Man from La Mancha, Karger is tilting at windmills as he dreams the impossible dream of an openly gay man becoming president of the United States.

But the Los Angeles-based candidate says he has role models and mentors who instilled in him the dream and the experience to make it happen. Before Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama competed for the Democratic nomination in 2008, there was Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman elected to Congress. Karger reminded Frontiers during a long lunch interview in West Hollywood on Jan. 18, that on Jan. 25, 1972, Chisholm became the first major-party black candidate for president and the first woman to run for the Democratic presidential nomination. Margaret Chase Smith, the first woman to serve in both houses of Congress, was the first woman to run for the Republican presidential nomination.

“I’ve always been a frustrated candidate, but I knew I could never run for office because I was gay and I was not out,” said Karger, chuckling at how he captured 137 more votes than anti-gay Rep. Michele Bachmann in the New Hampshire primary. Karger skipped the North Carolina primary and was barred from the ballot in Florida.

But watching the Jan. 19 CNN Republican presidential debate in South Carolina at home was frustrating, especially since much of the news centered on charges Newt Gingrich’s second wife Marianne made in an interview to ABC News that Gingrich wanted an “open marriage” so he could continue seeing his mistress Callista, now his third wife. Marianne said Gingrich wanted the new marital arrangement at the same time he was slamming President Bill Clinton’s morality for his affair. Gingrich has signed an anti-gay pledge, saying he believes marriage should be between one man and one woman.

But instead of showing contrition or publicly apologizing to his ex-wife, Gingrich blasted CNN’s John King for even asking the question.

“I watched the 17th debate tonight, which was difficult. I really want to be on that stage to talk about my moderate and inclusive views. The debates have gone from nine participants down to four, and for the most part every Republican is portraying himself as a far-right conservative. This is not where the country is, nor [where] the Republican Party should be heading. There should be a diversity of opinion in the debates as there is in the Republican Party,” Karger said in an email after the debate. “The ‘Newt Gingrich and ex-wife number two’ controversy is the classic ‘she said, he said.’ We know that he is a serial adulterer. Newt Gingrich is also a signator on the National Organization for Marriage’s 2012 Marriage Pledge. This identified hate group calls for a federal constitutional amendment to ban gay marriage across the land. Newt should be far more concerned with his marriages and not our ability to marry. I worked for Ronald Reagan, and I am sure that he would blast NOM and those candidates debating tonight for spewing their hate and divineness.”

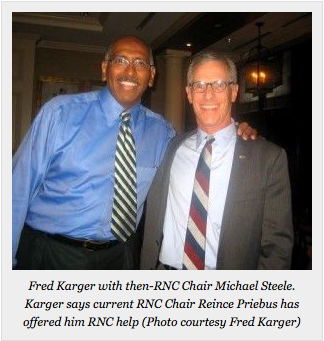

Indeed, Karger has considerable Republican credibility, but like fellow second-tier candidates former four-term congressman and former Louisiana Gov. Buddy Roemer and former New Mexico Gov. Gary Johnson, he has been denied the microphone and exposure the debates provide.

Karger has been an avid lifelong Republican. In 1977, Karger was hired by Bill Roberts to work at the Dolphin Group, a Westwood-based political consulting firm. Roberts and his partner Stu Spencer were famous for managing the election of Ronald Reagan for governor of California and his re-election in 1970, as well as working on the presidential campaign of Gerald Ford in 1976. Karger worked on George Deukmejian’s election as attorney general in 1978 and a slew of other federal, state and local campaigns during which he became an expert in opposition research, survey polling and other campaign techniques that the firm had pioneered.

“I learned from the best,” Karger said. “But I knew I could never run for office. It’s just like going to a wedding and sitting there knowing that could never be me up there. I just got used to it. So I worked for dozens of candidates—knowing that I could never run because of my deep, dark secret. Now, when I retired eight years ago, Jan. 1, 2004, I did what I’d been dreaming of doing—which is sleep late, no alarm, travel, worked a couple projects on my house.”

But people nudged him, saying he was too young to retire at 54. “I wanted to do something significant with my life, but I didn’t know what it was. Then I fell into this thing to save the Boom Boom Room in Laguna.” And though he was relentlessly teased because of the name of the bar, his life changed—he officially came out.

“I’d been out to family, friends and co-workers, but I’d never been out publicly,” Karger said. “The fact that I’d worked in Republican politics—I was no [closeted former Republican National Committee Chair Ken] Mehlman—not that stature. And I’d never been involved in anti-gay stuff. But I came out, and [Laguna Beach Mayor] Bob Gentry was my guide. He was my hero, the first openly gay mayor in the United States. He held my hand through the whole thing and gave me the courage to do it.”

Karger’s aggressive campaign to Save the Boom Boom Room also entailed taking on a multi-billionaire—who happened to be Mormon. A subtextual political pattern was developing.

When Prop. 8 came up in 2008, Karger knew he had to somehow be involved in beating back the initiative that would strip same-sex couples of their legal right to marry in California.

Karger met with leaders linked with the ‘No on Prop. 8’ campaign—including Equality California’s Geoff Kors, Freedom to Marry’s Evan Wolfson and Dewey Square campaign consultant Steve Smith—and told them he wanted to do opposition research independently from the campaign.

“I want to make it socially unacceptable to give massive amounts of money to take away the rights of a minority. It should not be bragging rights,” Karger said. “And there’s that famous story in the San Diego Union Tribune when Doug Manchester was gloating about his $125,000 contribution, and this Terry Castor—who ended up giving $693,000—said marriage between two men would create a ‘sick society.’ That pissed me off. So I decided to boycott Manchester.”

The boycott of the San Diego-based Manchester Grand Hyatt Hotel, launched in July 2008 in coalition with UNITE HERE Local 30, cost the largest hotel in Southern California $7 million in the first eight months. Karger’s description of how this and other boycotts and protests were organized are documented in a new book about his life, which uses as its title the catch phrase for his long-shot presidential campaign: Fred Who?

Through his Californians Against Hate organization, Karger noticed that people were contributing to the ‘Yes on 8’ campaign under different names. “They would give under their spouse’s name, so they put down ‘homemaker.’ I wondered—who are these people? $50,000 from a dentist?” That’s when the Mormon connection surfaced and he got national press. In September, the Wall Street Journal’s Mark Schoofs got on a Mormon conference call and heard orders for Mormons to give $25,000. His exposé prompted Karger to become more aggressive against the Mormons, “to try to stop them—which was too little too late, because that train had left the station.”

But by then he had developed a Mormon following, church members who would send him tips, some of which led to documentation. He discovered that the Mormon involvement in anti-gay marriage activities goes back to 1995. “They were in Prop. 22 [the anti-gay marriage initiative passed by voters in 2000]. They’ve been involved in every single election—invisibly—until we caught them. And they’ve not stopped because they don’t,” Karger said, noting that they continue to be involved, albeit invisibly. “They don’t back away until they get a revelation, and they’ve only had two of those under duress—when the IRS came down on them for polygamy and for not allowing African-Americans membership in the church. That was the most recent—1978. So I’m trying to deliver a revelation.”

Karger’s crusade to force the Church of Latter Day Saints out of the marriage discrimination business has caused the Mormons huge headaches. He filed a formal complaint with the California FAIR Political Practices Commission, charging the church with hiding how deeply involved it was in financially supporting the ‘Yes on 8’ campaign. After an investigation, the FPPC found the church guilty of 13 violations, for which they paid a fine.

Karger has called himself the “anti-Romney” candidate. He believes that a member’s obedience to the LDS Church supersedes loyalty to family and country, and hence, if Mormon Mitt Romney were to become president, he would have no choice but to obey an order from the president of the Mormon Church.

Karger has also gone after the Catholic-centric National Organization for Marriage, filing a formal ethics complaint in Maine about how they hide their political contributors as well. He turned over all his research to the Human Rights Campaign for its ‘NOM Exposed’ website, hoping HRC would follow up.

It was during the summer of 2008 that Karger first considered running for president. “In the middle of all this, I thought, ‘Wow, I’m certainly out now. So what’s stopping me from running for political office? Nothing.’ I want to make a difference, and that was my reason for becoming an activist—because I had a terrible struggle growing up. I had it better than most, because I wasn’t bullied and teased in school, but I had this shame and guilt and confusion all through high school and college and I went to shrinks to try to change. It was not an easy time. So I want to make it easier for younger people. I want to help others,” Karger said.

And even when closeted, that included gay activism. Karger met longtime LGBT activist David Mixner fighting the Briggs Initiative in 1978 when Karger was trying to make the ‘No on 6’ campaign bipartisan.

“First I got the Los Angeles County Young Republicans to come out and oppose it, which was a battle royale,” Karger said. “I was working by day for George Deukmejian for Attorney General, and then at night I would meet at Mixner’s apartment and do whatever I could to make this bipartisan.”

When progressive Democrat George McGovern mentioned the L.A. County Young Republicans at a ‘No on 6’ event, the media went crazy. But that was only a hint of what was to come. “I was part of this team with two guys—I was lower on the totem pole—Marty Dyer and Dennis Hunt, who had been boyfriends and worked for Reagan when he was governor,” Karger said. “They helped get Pete Hannaford involved in the campaign, and Hannaford set up the famous meeting with Mixner and [his consulting partner Peter] Scott with Reagan to ask for Reagan’s endorsement of ‘No on 6.’ We were behind about 2-1 in the polls. Hannaford, who was gay but not out then—this is 1978—said, ‘He’s not going to come out against it. The best we can hope for is that he’ll stay neutral.’ This is after Reagan had run in 1976 and narrowly lost to Ford and was gearing up to run in 1980. Well, after the meeting, Reagan told these guys, ‘I’m going to come out against it,’ and he did. He wrote an op-ed and the polls flipped.”

And that example of bipartisanship is one of the main reasons Karger is running for president. “What I believe is a necessity in our civil rights movement is to have that bipartisanship,” he said, citing GOP support for the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and the passage of marriage equality in New York. “I wish I had a dollar for every person who said, “How can you be a Republican?” But I’ve been trying to make that change in the Republican Party.”

But his efforts to do that have been stymied by the changing of primary and caucus dates—he has relied heavily on college voters—and getting into the debates. Some of that is a result of the media making decisions about the debate process. Moderate Republican political strategist Mark McKinnon points out in a new Harvard Kennedy School of Government report that Karger, Roemer and Johnson were systematically excluded by the media in a concern about ratings over democracy.

“The process of electing the next president of the United States is not a joke. That leads us to the question: Does the current primary debate process best serve voters, the candidates, the parties and the nation, or is there a better way?” McKinnon writes. “[A]s evidenced by the 2012 Republican primary process, control of the debates has been lost. That is a danger.”

In his report, McKinnon cites the selection criteria for who gets in the debates as a significant problem. “Because of an absence of any central organizing entity or party control, there were no clear or consistent criteria for qualifying for the debates. The criteria changed from debate to debate.

“Fred Karger has gone further than either of his excluded colleagues, filing lawsuits alleging the violation of federal election campaign laws against a pair of debate sponsors that kept him off their stages,” McKinnon writes. “The first case charges the Iowa Faith and Freedom Coalition of exclusion from their March 7, 2011, Presidential Forum ‘based on the subjective prejudices of the IFFC’s president, Mr. Steve Scheffler.’ Citing an email exchange between himself and Scheffler, Karger claims that he was not invited to the forum based on his support for gay marriage and general advocacy in favor of the ‘radical homosexual community.’

“The second case,” McKinnon continues, “accuses the Fox News Channel and its owner News Corporation of discrimination in spite of Karger meeting the necessary polling numbers for the Aug. 11 debate. ‘It appears that because I met their originally stated criteria, Fox News changed their criteria in order to exclude me,’ concludes Karger.”

With the Republican candidates steadily whittling down, Karger hopes to get on the debate stage in Michigan, where he will be one of the last standing GOP presidential candidates on the ballot.

Whether he gets on the stage or not, Fred Karger has paved the way for other LGBT people to dream the impossible dream of one day being elected president of the United States.